There is little doubt that the embryo of the town of Dorchester stood within the great ramparts of Maiden Castle, and was already a place of consequence when the Romans landed in Britain. As years advanced and as times grew more peaceful, the Celts who crowded the pit dwellings on the hill came down to the river-side and founded there a town upon the site of which the Dorchester of the Domesday Book and the Dorchester of to-day arose in turn. The capital of the county lies on the great Roman road, the Via Iceniana, and there is evidence to show that the Romans made of Durnovaria as they called the place one of their chief cities of the South. They carried roads from out of it in many directions, and built a massive wall to shut it in, of which a fragment exists to this day.

Very numerous indeed are the Roman remains which have been found in and about Dorchester. The town, as Thomas Hardy says, "announced old Rome in every street, alley, and precinct. It looked Roman, bespoke the art of Rome, concealed dead men of Rome. It was impossible to dig more than a foot or two deep about the town, fields, and gardens without coming upon some tall soldier or other of the Empire, who had lain there in his silent, unobtrusive rest for a space of fifteen hundred years." In the museum are piles of Roman Relics. The town itself still conforms to the lines laid down by the builders from Rome a town of four main streets, North, South, East, and West. On the outskirts are a famous Roman amphitheatre, as well as two British camps, Poundbury and Maiden Castle, which both show the signs of Roman occupation.

Dorchester has never been insignificant. In the days of Edward the Confessor it boasted of no fewer than 172 houses or huts, while by the time King Henry VIII. ruled in the land the number of dwellings had increased to 349.

The history of the town differs little from that of other English settlements endued with ambition. It was duly ravaged by the Danes, received unappreciated visits from King John, was the scene of many hangings, drawings, and quarterings, was laid low by the plague, and was more or less destroyed at sundry times by fire.

The most notable fire broke out at two on an August afternoon in 1613. It began at the house of a tallow chandler, and at a time when most of the townsfolk were unfortunately away, being busy in the harvest fields. It destroyed 300 houses and two out of the three churches of the place, St. Peter's alone being spared. Considerable use was made of this conflagration to collect money for the building of a hospital and a house of correction, it having been pointed out that the fire had arisen because " it had pleased God to awaken them [the inhabitants] by this fiery trial." The townsfolk, who had been thus rudely aroused, provided the money, but at the same time built a brew-house, intending that out of the profits derived from the sale of beer the hospital should be maintained. It is doubtful if at the present day the charitable public would be disposed to devote a portion of the Hospital Sunday Fund, for example, to the purchase of remunerative public-houses. The repentant folk of Dorchester, in their character of "brands snatched from the burning," had still unregenerate conceptions of business and of public morals. They failed to see the impropriety of tending the sick with the money derived from making them drunk.

There were minor fires in the town in 1622, 1725, and 1775.

It is no matter of wonder, therefore, that the city fathers developed a dread of fire. On May 13th, 1640, for instance, the churchwardens of St. Peter's were ordered to provide " tankards [i.e., leather buckets] to be hanged up in the church." In June, 1649, it was proposed to expend £30 to £40 for buying of a brazen engine or spoute to quench fire in times of danger." This engine was a brass syringe, held up by two men and worked by a third. In December, 1653, we find that two officials were wisely told off for each parish, " to see and view iff there bee any badd or dangerous chymnyes or mantells and to see that all persons keepe their wells, buckets, ropes, tanckets, malkins, and ladders fit to make use of uppon occasion."

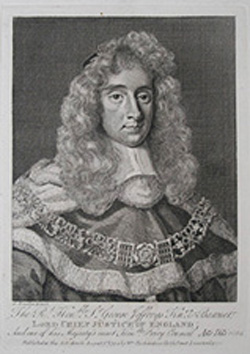

George Jeffreys (1645-1689) - 'The Hanging Judge'

George Jeffreys (1645-1689) - 'The Hanging Judge' In the Great Rebellion Dorchester was so strong for the Parliament that it is described by Royalists as being " the seat of great malignity." In 1642 the town was fortified at great expense with walls, forts, and platforms. When, however, the Earl of Carnarvon, on behalf of the King, approached the stronghold, the courage of the defenders abruptly vanished, and, without firing a shot, they surrendered the town, with all its arms, ammunition, and ordnance. For many months this " seat of great malignity " suffered extremely, and was no doubt woefully uncomfortable. It was taken and retaken, so that the nerves of the inhabitants can only have been restored when Dorchester was finally seized by Lord Essex for the Parliament.

THE BLOODY ASSIZE Page 345

It was in this town, on September 3rd, 1685, that Judge Jeffreys opened in earnest his Bloody Assize. The purpose of his visit was to try all those who were suspected of being concerned in Monmouth's mad rising, and to pass sentence on such as were found guilty. The Duke of Monmouth, it may be remembered, was captured at Horton on July 8th, and executed on Tower Hill on July 15th. Macaulay has thus described the opening of the Assize : " The Court was hung, by order of the Chief Justice, with scarlet ; and this innovation seemed to the multitude to indicate a bloody purpose. It was also rumoured that, when the clergyman who preached the assize sermon enforced the duty of mercy, the ferocious mouth of the Judge was distorted by an ominous grin. These things made men augur ill of what was to follow. More than 300 prisoners were to be tried. The work seemed heavy, but Jeffreys had a contrivance for making it light. He let it be understood that the only chance of obtaining pardon or respite was to plead guilty. Twenty-nine persons, who put themselves on their country and were convicted, were ordered to be tied up without delay. The remaining prisoners pleaded guilty by scores. Two hundred and ninety-two received sentence of death. The whole number hanged in Dorsetshire amounted to seventy-four." From a paper by W. B. Barrett, in the Proceedings of the Dorset Field Club (Vol. V. page 99), it would appear that the returns of Jeffreys's work in the county are as follows :

-

Presented at the Assizes 312

Executed 74

Transported ... ... 175

Fined or whipped ... 9

Discharged ... ... 54

Jeffreys was thirty-seven years old at the time of the Great Assize. He remains notorious in history as a corrupt judge, a foul-mouthed, malevolent bully, and a fiend who delighted in cruelty. He was a drunkard, a man of the coarsest mind, with a ready command of blasphemous expressions. I am a little disposed to think that the violence of this contemptible being was in some part due to disease, for he is said to have been " tortured with the stone." His portrait, by Kneller, is singularly unlike any conception that may be formed of the judge of the Bloody Assize. It shows a slight man, clean-shaved according to the custom of the time, with a refined, gentle, and intelligent face and dreamy eyes. For his hideous work in Dorset and Devon Jeffreys was made Lord Chancellor of England. His end was as horrible as his life had been. He was committed to the Tower of London, where he died at the age of forty-one a diseased, hounded, and accursed wretch. The last sound of the outer world that broke upon his ear, as he crossed the drawbridge of the prison, was " the roar of a great city disappointed of its revenge."

There are two relics of Jeffreys still in Dorchester. In the West Street is a picturesque timber house with an overhanging story. It is now a shop, but it was in this building that the infamous judge lodged when he visited the town for the purpose of the Assize. In the Town Hall also is preserved his chair, a bland and homely piece of furniture, with no suggestion of villainy about it. To these relics may be added a third. In the museum is a spike from the porch of St. Peter's Church, upon which was set the head of one of Monmouth's rebels to blister and to blacken in the sun.

Dorchester shows by its records [To be found in the Proceedings of the Dorset Field Club,] that it was always jealously mindful of the personal morals of its inhabitants, as well as of its own dignity. For example, in June, 1632, Robert Foot was charged with being " severall tymes drunke and wishing that fire and brimstone would fall on this town, it being sufficiently proud." For this expression of his opinion as to the pride of the town and the best means of curbing it Mr. Foot was ordered to prison, " to be sett close to worke." Again, Mr. W. Hardy, gentleman, who facetiously described himself to the authorities as " dwelling everywhere," was fined for calling the constables " a company of damnd creaturs." Scolding was severely punished. In January, 1632, four women are declared to have " spent the most part of two daies in scolding.' For this long-sustained flow of unpleasant speech they were ordered to be " plounced " that is to say, to be ducked.

It is well to note that the magistrates of the town were very indulgent towards women who had drawn upon themselves the terrors of the law. Thus, on May 6th, 1631, " Mary Tuxberry, for scoulding at the sergeants when they did goe about for mersements [fines] , was ordered to be plounced when the wether is warmer." As the "scoulding" took place early in May, Mrs. Tuxberry must have felt that she was treated with every consideration a lady could expect. Alice Cox too, in the same year, was ordered to be placed in the stocks for drunkenness, but the sentence was " forborne for a week, she being unfit then to be stocked, and since was stocked." Here it will be seen that time was thoughtfully granted to Alice Cox to recover from the nervous depression consequent upon her indulgence.

The rulers of Dorchester were very strict regarding the proper observance of the Sabbath, as will be seen from the following records: On January17th, 1629, Hugh Baker was put in the stocks for two hours for leaving church before prayers were over. On October 12th, 1632, Ursula Bull was fined one shilling for absence from church, although "she saith she was amending her stockings." A very unseemly outrage is dealt with in the following entry of August 29th, 1631 : "Jo Kay and Nicholas Sims did play at All Saints' in sermon time and laughe, and Sims did stick Kay a box on the ear and carry themselves very unreverently." For this offence they were both committed to prison. Of the many culprits dealt with at Dorchester for neglect of the Sabbath, I think that J. Hoskins showed not only the most enterprise, but also the most versatility of character. On January 2nd, 1634, Mr. J. Hoskins the Abandoned went out of church before the end of the service. He went first to a neighbour's house to warm himself. Thus refreshed, he betook him to the " Broad Close " to serve cattle. Here the impious Hoskins found a bull, and promptly put him into a pound and baited him with a dog. Hoskins, when he had exhausted the pleasures of this sport, returned to the church and to his interrupted devotions. His absence, however, had been observed; possibly he chuckled audibly to himself over the bull-baiting during the final prayers. Anyhow, he was charged on the Monday and fined one shilling, the punishment evidently of a sympathetic judge.

The town authorities were very liberal also in the treatment of their sick. In the annals of 1640 is an order to pay Peter Sala Nova £5 for cutting off Giles Garrett's leg. About this period it is noted that Master Losse received £8 per annum "as fee as physician in taking care of the poore of the Towne." When occasions arose which were beyond the powers of Master Losse a specialist was called in. Thus in 1654 is an order " for the widow Devenish to be sent down to Master fforester for cure of her distemper." This cost no less than £15 "out of the town purse £5, out of her owne state £5, out of honest people's purses £5. On occasion a lady doctor was employed by the town. Her name was Canander Huggard. She does not appear to have been a lady of great professional initiative. It is noted, for instance, that on January 5th, 1654, she was paid £3 not for her own advice but " for finishing the great cure on John Drayton otherwise Kense."

Dorchester in olden times must have been, like many other country towns, a most picturesque place. The old Town Hall, for example, was a quaint and dignified building, with an ample balcony from which to address the crowd. There were, Hutchins says, some Flemish buildings of plaster and timber in the Corn Market and about St. Peter's Church. In the centre of the town stood the Cupola or market-house. " It was removed in 1782, its situation being found inconvenient on account of the great increase of travelling. It was built in the form of an octagon, supported by eight handsome pillars, and covered on the top with lead, on which formerly stood a little room capable of containing ten persons, and made use of for some of the corporation to meet on particular business. It was encompassed with balustrades, and was in the form of a cupola, whence it had its name." In the North Street was a footway made for passengers, paved with square stones and guarded by posts. Here also was " the Blind House for confining disorderly people for the night."

The houses crowded casually into the road, so that the streets were much narrowed. At the corner of South and East Streets opposite to the present Corn Exchange two dwellings stood so near together that their upper rooms joined over the highway, which was thus converted into a mere passage. The streets were not only narrow, but very untidy, and covered by uncouth cobble-stones. The kennel was full of garbage and miscellaneous litter. The houses were mostly of timber, with roofs of thatch. They were rich in gables and dormers, in windows with diamond panes, in outside galleries, and in overhanging stories. There were inns too whose stable yards were the centres of the bustle of the town as well as of the gossip of the county. Before the red-curtained bow windows stood a drinking trough for horses. The shops were low and dark, so that in fine weather the goods were set out by the road side, while in each of the little marts the tradesman could be seen busy at his trade.

To complete the conception of the bygone town the streets must be pictured as filled by people in the costumes of past days : by the yokel in his smock, by the soldier in the uniform that Hogarth drew, by the sailor with his pigtail. Here would come by a company of sheep guided by a shepherd, then three pigs driven by an old woman, a pedlar with a box of bright ribbons, a wandering knife-grinder, a donkey laden with baskets full of geese, and a man in black, who might be one of the ushers at the school. Now and then a sedan chair would swing across the road, especially when the days were wet ; and on rarer occasions a carriage of some of " the quality " would lumber by, bumping over the ruts an splashing with mud the children who ran by the side of it.

The Dorchester of to-day is a bright, trim town, which, so far as its four principal streets are concerned, can claim to be still picturesque. The ancient houses are being gradually replaced by new, while all around the grey old town are arising those florid suburbs which in days to come will make the present era famous for architectural ugliness.

At one time the country came up to the very walls of the town. The North Street ended abruptly in a mill by the river, the South Street came to a sudden end in a cornfield. The East or Fordington side of the town remains unchanged in this particular, so that it is from this quarter that the approach to Dorchester is the most pleasing and the most reminiscent of past days. Here the water meadows reach to the very garden hedges and to the actual walls of houses. Indeed, cows pasturing by the river might shelter themselves from the sun under the overhanging story of one of these ancient dwellings on the fringe of the town. This quarter of Dorchester is well displayed in a beautiful water-colour drawing by Walter Tyndale in Clive Holland's Wessex. London, 1906.

In Hutchins's History of Dorset is a plate showing Dorchester as viewed from the East, from near a bridge over the Frome called Grey's Bridge. The date of the plate is 1803, and it is interesting to observe how very little the aspect of the place as seen from this point has altered in these one hundred and three years.

Dorchester was long prevented from extending its boundaries by being hemmed in on nearly all sides by Fordington Field, a wide stretch of land of over 3000 acres, " held under the Duchy of Cornwall in farthings or fourthings [the quarter of a hide [A measure of land enough to support a family] or caracute [As much land as could be tilled with one plough (with a team of eight oxen) in one year.] from which it derives its name in the original form of Fourthington." [ Murray's Wilts and Dorset, Page 518] The tenure of land in this field was hampered until recently by such restrictions as to make development of the town beyond its ancient limits difficult or impossible.

One of the most beautiful features of Dorchester is its ceinture of green, for on three sides it is surrounded by avenues of trees of sycamores, limes, and chestnuts. On the fourth side runs the River Frome through reedy meadows. These avenues, called "The Walks," were planted between 1700 and 1712 on the lines of the ancient walls. Until quite recent years the Walks formed the outermost boundaries of the town, beyond which no house ventured to stray. The town indeed, as I recollect it, was still " huddled all together, and shut in by a square wall of trees, like a plot of garden ground by box- edging," as a character in one of Hardy's novels observes. These formal avenues or boulevards give to Dorchester an uncommon air and a little of the aspect of a foreign town. The principal roads, too, which approach the capital enter it with great solemnity through avenues of fine trees.

The best view of the town is from the top of the West Street. From this height the town slopes downhill to the river. There is a long, straight, yellow road, with a line of irregularly disposed houses on either side of it. No two are of quite the same height. They favour white walls, ample roofs, bow windows, and stone porticoes. Where there are shops there are patches of bright colour, striped sun-blinds, and a posse of carriers' carts. Over the house-tops rise the stolid tower of St. Peter's, the clock turret, and the pale spire of All Saints' Church. Then, at the far-away foot of the slope, the diminished road can be seen running out into the green water meads, to be finally lost among the trees of Stinsford.

In the exact centre of the place, and forming, as it were, the Arc de Triomphe of Dorchester, is the town pump very large, very parochial-looking, and very self-conscious. Near it is the handsome and venerable church of St. Peter's, which has witnessed and survived the great dramatic events in the town's history the fearful fire of 1613, the alarms of the Great Rebellion, and the horrors of the Bloody Assize.

The church is well preserved, even to its south door, which dates from the late Norman period. In the porch, in front of this door, lies buried the Rev. John WHITE who is better known as the "Patriarch of Dorchester." Born in 1575, he became the rector of Holy Trinity in 1606. He was a masterful old Puritan, and an absolute autocrat in the town. During his rule there was never a beggar in his parish. Fuller says of him that " he had perfect control of two things his own passions and his parishioners' purses." He was, curious to relate, one of the founders of Massachusetts, for in 1624 he despatched a company of Dorset men to that remote part. He raised money for them, procured them a charter, and sent them out their first Governor in the person of John Endicott, of Dorchester. That official sailed for New England in 1629 in the George Bonaventura. In 1642 a party of Prince Rupert's horse broke into John White's house, and stole his books. He fled to London, where he became rector of Lambeth. When peace was restored he returned to Dorchester, and died there in 1648.

The church contains many ancient monuments, some of which have been described as " noble " or " superb," and others as merely " very lofty." A memorial which can claim to be ridiculous is one to Denzil Holies. He it was who, entering Parliament in 1624, was one of the "five Members" whom Charles accused of high treason and attempted to arrest in 1642. He was also one of the redoubtable gentlemen who held the Speaker forcibly in his chair whilst certain resolutions in which he was interested were passed. This active person is represented as reclining, with a fine air of boredom, on a cushion. He is dressed in the costume of an ancient Roman. On his feet are the sandals of the days of the Caesars, while on his head is the full-bottomed wig of the time of the Stuarts. He is attended by unwholesomely fat cherubs, who are weeping.

Outside the church is an excellent statue to William Barnes, the Dorset poet. On the pedestal are engraved these lines from one of his own poems :

" Zoo now I hope his kindly feaceIs gone to vind a better pleace ;

But still wi' v'ok a-left behind

He'll always be a-kept in mind."

By the side of St. Peter's is the County Museum, where is to be found one of the most interesting collections out of London. Many of the objects in the museum have been already referred to. Here are to be seen leg-stocks and handstocks, a collection of most devilish man-traps, and certain of the wooden reeve staffs of Portland, on which, by means of notches, details as to the tenure of land were recorded. Here too the curious will find the blade of a halberd which had been converted into a sword by a smuggler, from whom it was taken at Preston in 1835. Furthermore, amidst relics of Roman days and of prehistoric man will be seen the humstrum, an old Dorset viol, which has long since passed away, but which at its best was hardly worthy of a tribe of Hottentots. Of this quaint musical instrument Barnes has written in the following strain :

" Why woonce, at Chris'mas-tide, avoreThe wold year wer a-reckon'd out,

The humstrums here did come about,

A-sounded up at ev'ry door.

But now a bow do never screape

A humstrum any where all round,

An' zome can't tell a humstrum's sheipe,

An' never heard his jinglen sound."

Very handsome is the ringers' flagon in the museum, from the belfry of St. Peter's Church, with the date 1676 ; very horrible are two leaden weights, marked " MERCY," which were made by a kind-hearted governor of the gaol to be tied to the feet of a man who was hanged for arson in 1836, and who was so slight that the governor thought he would be long in the strangling.

In the South Street is the grammar school, founded by Thomas Hardy, of Melcombe Regis, in 1569. This worthy, who lies buried in St. Peter's Church, was one of the family of the Le Hardis of Jersey, from whom Nelson's captain was descended. " After the lapse of three centuries his crest a wyvern's head is still worn on the cricket caps of the Dorchester alumni." The original schoolhouse was newly built in 1618, after the fire of 1613. This building I had reason in my youth to know only too well. It was pulled down in 1879, when the present edifice appeared in its stead. Through all its vicissitudes the school has preserved a certain stone in the wall upon which are carved Queen Elizabeth's arms, supported by a lion and a wyvern, and the date 1569.

Next to the school is " Napper's Mite," a small almshouse, with a charming little cloister and enclosed garden, founded by Sir Gerard Napier in 1615.

In the same street, but on the other side of the way, was the school kept by William Barnes. He came to Dorchester from Mere, and the dwelling in question was the third he had occupied since he tried his fortune in the larger town. It was here, at a tender age, that I had my first experience of school life. My recollection of the poet and philologist is that of the gentlest and most kindly of men. His appearance was peculiar. He had white hair and a long white beard, and always wore knee breeches and shoes with large buckles. Out of doors he donned a curious cap and a still more curious cape, while I never saw him without a bag over his shoulder and a stout staff. During school hours he was in the habit of pacing the room in a reverie, happily oblivious of his dull surroundings. I remember once that some forbidden fruit of which I was possessed rolled across the schoolroom floor, and that I crawled after it in the wake of the dreaming master. He turned suddenly in his walk and stumbled over me, to my intense alarm. When he had regained his balance he apologised very earnestly and resumed his walk, unconscious that the object he had fallen over was a scholar. I have often wondered to which of his charming poems I owed my escape from punishment.

Just to the South of the town, on the Weymouth road, stands Maumbury Rings, a Roman amphitheatre, which is by far the finest work of its kind in Great Britain. It is an oval earthwork covered by grass, the enclosing rampart of which rises to the height of 30 feet. On the inner slope of this embankment the spectators sat. The arena measured 218 feet in length by 163 feet in width, while the amphitheatre itself will accommodate from ten to twelve thousand spectators. "Some old people," writes Thomas Hardy of this place, "said that at certain moments in the summer time, in broad daylight, persons sitting with a book, or dozing in the arena, had, on lifting their eyes, beheld the slopes lined with a gazing legion of Hadrian's soldiery, as if watching the gladiatorial combat, and had heard the roar of their excited voices ; that the scene would remain but a moment, like a lightning flash, and then disappear. It was related that there still remained under the south entrance arched cells for the reception of the wild animals and athletes who took part in the games. The arena was still smooth and circular, as if used for its original purpose not so very long ago. The sloping pathways by which spectators had ascended to their seats were pathways yet. But the whole was grown over with grass, which at the end of the summer was bearded with withered bents that formed waves under the brush of the wind."

Until 1767 the public gallows stood within this tragic enclosure. It was here that, in 1705, Mary Channing met her fearful fate. When a mere girl she was forced by her parents to marry Richard Channing, a grocer of Dorchester. Her life with him was dull, for her heart was elsewhere, and she longed to be free. At last she poisoned him, they said, by giving him white mercury, first in rice milk and then in a glass of wine. She was found guilty and condemned to death, but pleaded pregnancy. She was removed to prison, where her child was born eighteen weeks before she died. On a spring morning in 1705 Mary Channing, still only nineteen years of age, was dragged to the arena of Maumbury Rings, clamouring forth her innocence all the way. From the centre of this arena the solitary girl faced a crowd of ten thousand men and women. Here she was strangled by the public hangman and then burned, whereupon the virtuous and Christian folk who had walked miles to see her die returned home satisfied.

There are two famous earthworks outside Dorchester with which the dawning history of the town is intimately concerned. These bluff strongholds of Poundbury and Maiden Castle appear to have been made by the Britons, and to have been occupied and modified later by the Romans. Poundbury stands on high ground above the river. In early days there was to the North of the encampment a great lake, a mile wide, fed by the Frome. Hence it is that to the North there is only one rampart to defend the enclosure. A well-marked trackway leads out of the north-west corner of the earthworks.

Maiden Castle the Mai-Dun or Hill of Strength stands some two miles South of Dorchester, in a solitude on the downs not far from the Roman road. Whether it was a fortified town, or a great camp, or a city of refuge matters little ; it remains to this day the most stupendous British earthwork in existence. It stands on the flat summit of a hill, where it covers an area of no less than 115 acres. The enclosure within the ramparts measures alone 45 acres. This gigantic structure was made by men who worked with horn picks and with hatchets of stone or bronze. When the inhabitants left the camp centuries ago they left it for ever. It remained as desolate as a haunted glen. It became a solitude; no man meddled with its walls, so that its great valla became merely shelters for sheep. Thus it is that Maiden Castle survives in perfect preservation, an astounding monument of the work pf those busy Celts whom the Romans on their coming found in the occupation of England.

The defences follow the natural lines of the hill, and consist of three or more ramparts, 60 feet in height and of extreme steepness. It is not an easy matter even now to gain this Celtic fortress, unless an entry be made by one of the four gates, and these in turn are made hard of approach by overlapping ramparts and labyrinthine passages. The perimeter of this unique stronghold of the Round Barrow Men is no less than two and a quarter miles.

Maiden Castle, to the mind of the Celt, lacked nothing in perfection as a site for a founding of a town. It realised to the fullest his ideals of a home. Here is a hill on an open down, a height so commanding that none can approach it unseen, a place ready to defend, with all around it grazing land for sheep and no patch of cover for wild beasts or the creeping foe. At its foot are the lowlands of the Frome, where could be grown such crops as the man had knowledge of, and where he could find fish for his eating and the wherewithal to build his mud and wattle huts. In primitive grandeur in the grandeur of the sheer cliff and the Titanic rock there is nothing in Dorset to surpass this hill-town, this city of refuge, with its grasscovered ramparts rising, tier above tier, against the sky-line.

CHAPTER XXIII - The Environs of Dorchester

FORDINGTON is an appendage to Dorchester, not a suburb. It is an independent village, which many centuries ago attached itself parasitically to the town. The Church of St. George at Fordington is an interesting building, whose tall, battlemented tower is the first token of Dorchester that meets the eye when the town is approached from afar. Within the walls are Norman arches and pillars, a curious holy water basin, and a stone pulpit bearing the date " 1592, E.R."

Over the Norman door on the south wall is an archaic carving purporting to represent the performance of St. George at the battle of Antioch in 1098. The saint, seated upon a horse, is attacking certain knights in armour in a very casual and supercilious manner. These knights are really Saracens or Paynims, although they are clad in Norman armour of the kind shown in the Bayeux tapestry. St. George grasps a spear decorated by a flag. He has thrust the end of the spear into the mouth of a semi-prone idolater, who is trying to pull it out with his right hand with obvious anxiety. Other Paynims are lying about dead and much bent up. Their spears too are broken. Certain of the enemy are kneeling, and with canting looks are praying for mercy.

Away to the east of Fordington is the little village of Stinsford, the "Mellstock" of Hardy's story, Under the Greenwood Tree. The church and the churchyard are both charming and very typical of the old-world Dorset village.

Near by are the two dainty Bockhampton hamlets, the one by the bank of the stream, the other on the fringe of the Great Heath. At Upper Bockhampton an ancient cottage is pointed out which is almost hidden from sight by the bushes of its old garden on the one hand and by the slope of the downs on the other. It is the birthplace of Thomas Hardy.

On this side of Dorchester too are the lovely village of West Stafford, with a church and rectory good to see, and the quaint little settlement of Whitcombe, which is content to remain as it was a century or so ago.

About a mile and a half to the north-west of Dorchester, in the Frome valley, is Wolfeton House, for long the seat of the Trenchards and a fine example of the domestic architecture of the reign of Henry VII. The house was built by Sir Thomas Trenchard in 1505, and was remodelled by another Trenchard in the time of James I. The gate-house is supported by circular towers with conical roofs. The part that this house played in the fortunes of the noble family of Bedford has been already referred to. Thomas Hardy, in his Group of Noble Dames, describes Wolfeton as "an ivied manor house, flanked by battlemented towers, more than usually distinguished by the size of its mullioned windows."